Clubs, catalysts for progress

A first question arises: Who invented the internal combustion engine, a lightweight mechanism that could power both boats and automobiles? A handful of neatly bearded gentlemen in black hats, gray coats and ties would raise their hands in unison. They are from Italy (Barsanti), Germany (Otto, Daimler, Maybach) and France (Beau de Rochas, Lenoir, Forest), engineers, inventors and modern-day adventurers, as if escaped from the pages of a Jules Verne novel.

Thanks to them, a few examples of these modest mechanisms are installed on slender hulls of boats that skim along at a few knots, sputtering as they go, fine-tuning their performance. It is exhilarating, genuinely new, and entertaining, especially when several boats take to the water together to see who goes faster (or breaks down less).

Once these rare engines become more widespread, who can truly claim to have invented motorboating? The answer is no longer a handful of feverish inventors working in isolation, but a whole cohort of gentlemen, often from high society, determined to play their part in the great spectacle of motorization unfolding on the roads and on the water. They are the founders of the many clubs that emerge at the turn of the 19th century, across Europe and the Americas. While the rise of sports associations, an English innovation, is already well known to sailing enthusiasts from the 1840s, the creation of new social venues and “societies of encouragement” devoted to the pioneers of mechanical propulsion serves a new purpose. Some established institutions, such as the Yacht Club de France (founded in 1867), begin, more or less willingly, to welcome advocates of the mechanical trend. Although they move in the same social circles, the differences between sailing and motoring practices quickly lead to the formation of dedicated organizations. Without them, the wealthy gentlemen captivated by the challenge of mechanized progress would have lacked the competitive spark that drives technical advances and innovation. Moreover, the emergence of these motorboating clubs, often led by prominent public figures, provides both social legitimacy and official recognition, allowing them to navigate legally – and even patriotically.

While the Automobile Club de France is created in Paris in 1895, the Hélice Club de France registers its charter the following year. As the world’s first motorboating club, its example is quickly followed in the early years of the new century by most industrialized nations. Motorboating and the automobile are closely linked, each thriving in its own domain. The promotion of one benefits the other, with high stakes and great promises for the future, when the startups of the day include names like Delahaye, Panhard, Peugeot, Renault and Fiat.

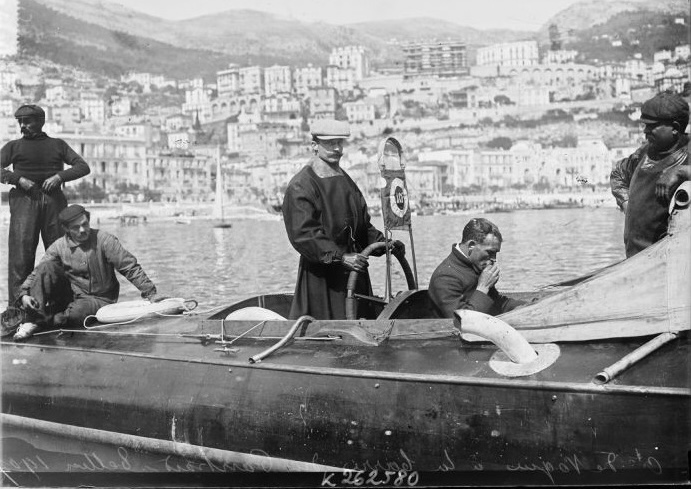

After the first Paris to the Sea rally of 1897, then the exploits of the boats invited to the Paris Universal Exhibition in 1900, and the incredible success of the first Monaco meeting in 1904, more and more initiatives begin to be seen, supporting not only competition, but also nautical tourism. Many participants in events such as the Monaco race belong to the category of “cruisers” or “davits boats”, with no pretension to speed, heralding the rise of a motorized leisure boating culture that will become increasingly accessible. Various private and public initiatives will support this development, driven by the clubs. In its February 1904 issue, the monthly journal of the powerful Touring Club de France (TCF) already declares: “Considering that navigation on rivers and canals and coastal cruising are expected to expand rapidly and significantly, mainly through the application of mechanical engines, our Association wishes to take an interest in this new form of tourism. […] The Council has decided to create a Committee for Nautical Tourism”. The TCF will then embark on a gradual democratization of motor yachting, which will continue for several decades, thanks in part to the advent of more affordable outboard propulsion.

Between the two World Wars, the promotion of France’s natural heritage, from its lakes to rivers and coasts, also inspires numerous initiatives that are supported by clubs and vigorously backed by major automobile brands. For instance, in the 1920s, Peugeot launches a surprising initiative to harness the vast potential of this new leisure market, introducing not only a full range of boats, but also services, guides and practical solutions for passing through locks more easily. During this same decade of boundless enthusiasm, the 1920s see the Yacht Moteur Club de France set up the first boat shows in Paris, where various clubs showcase their activities, while reassuring newcomers through their extensive experience.

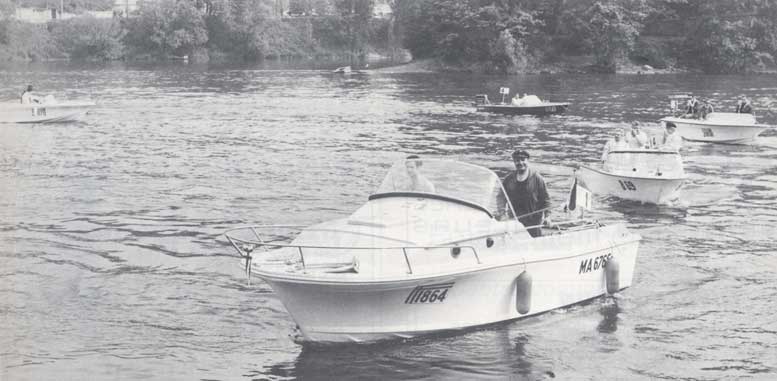

30 years later, in 1955, still at the foot of the Eiffel Tower, the same Y.M.C.F. rekindles the spirit of the early days by launching an endurance race that will become known around the world: the Paris Six Hours. As unforgiving as it is unmissable for the prestige that surrounds it, the Six Hours becomes the testing ground for as many hulls, materials, engines and transmissions as national and international builders can invent, particularly during the 1960s and 1970s, when recreational motorboating opens up to a far wider audience than ever before. This is the price of progress, sometimes even at the cost of racers’ lives. The Yacht Club du Rhône, very active from the mid-1930s, also plays a key role in this story, with an original event – the “Lyon-Marseille-Cannes” race – held on the river before the war. It goes on to organize, with great success, annual raids that end in Marseille until the early 1960s. Changing navigation conditions will later give rise to annual family cruising rallies through to the mouth of this legendary river.

This enthusiasm recalls the sporting and technical prestige of the equally formidable Pavie-Venice raid, organized since 1929 by the very active club in the city where it set off from, along a river route full of challenges. Welcoming the most accomplished racing pilots, this event also opens up, through its “Sun Cruise” section, to casual boaters looking to enjoy a journey that is both educational and unforgettable along this iconic route. The Pavillon d’Or, created by the Deauville Yacht Club in 1949, follows the same approach to promote high-level, non-competitive motorboating that encourages safer and more comfortable navigation.

oday, after so much energy has been expended, what is new under the sun after more than a century of engine development? Perhaps surprisingly, the most striking example of a spectacular transformation of the original vision once again takes us to Monaco. In April 1904, “in order to study all possible applications of the light engine for navigation”, 25 presidents of automobile clubs and yacht clubs from France, Europe and America sponsored the world’s first major motorboat competition, at the invitation of the International Sporting Club. It is a resounding success and continues to be held over the next 20 years or so. While the press and the general public of the time focused on the exploits of the headline acts and the most powerful racers, the more discreet events reserved for pleasure craft were no less remarkable. The engines and equipment on board these boats became increasingly reliable from year to year, thanks to the testing ground provided by the timed Monaco-Nice-Monaco course. One hundred years later, the principality’s Yacht Club decided to take on a new challenge by creating the Monaco Energy Boat Challenge, “an event that embodies the future of environmentally responsible yachting through bold projects and fruitful collaborations between students and professionals”. Its eclectic lineup includes zero-emission categories such as Energy, Solar and Open Sea, aiming to “reinvent boating and transform an entire industry”. As a small nod to history, the hull of the prototype designed by ENSTA, a leading Parisian engineering school, features the emblem of the Yacht Moteur Club de France, which is supporting this venture…

Unmatched in its scale and influence was Monaco’s initiative at the beginning of the 20th century; unmatched it remains today – an event capable of attracting 42 delegations and a thousand students from 20 different countries. The same boundless creativity has clearly not aged a day, on land or on the water, while the inclusion of women alongside men has greatly enriched the teams’ collective talent. Only the dress code has truly changed. The T-shirt has replaced the stiff collar, and the baseball cap, the hats that were once seen on every head, whether crowned or not.

Gérald Guétat