100 Years of Boat Shows in Paris

It was a small wooden sloop, barely 9 meters long. It did not have a record of victories, or any long-distance reputation. But it was ahead of its time. Above all, it was named after a legend: Alain Gerbault. It embodied the ideas of France’s first recreational sailor. Gerbault enjoyed considerable fame at the time: he had dared to sail solo across the Atlantic. A feat no Frenchman had ever achieved before him. “His” boat was born from the drawings of Victor Brix, a White Russian who had taken refuge in France, and was built as a small series.

Gerbault did not hesitate long to give this modest Marconi rig its full name. After all, auto manufacturers had been naming their creations for nearly 30 years, although without seeing the need to attach their first names to their surnames.

But Alain Gerbault was a hero, a brand by himself. A decorated World War I pilot, a champion bridge and tennis player, a dandy of Parisian nightlife, and now an offshore recreational sailor, he embodied the youthful spirit of the “Roaring Twenties”, as later generations would call these seasons of revenge on the horrors of 1914-1918.

A show for cars and boats

What better symbol to attract Parisians looking for a sense of escape and princely leisure than to exhibit the Alain Gerbault on the banks of the River Seine, as part of the Paris boat show? In October 1926, just steps from the Grand Palais, where the auto show was taking place at the same time, the first major international meeting of recreational navigation opened. Its organizers envisioned this event as the perfect complement to the display of automobiles – and even aircraft – just a few dozen meters above them. Parisians, fascinated by the convertibles and flying machines, needed only to descend to the quays to visit or see sailing and motor boats in action. The idea was brilliant, the intuition prophetic. The show was a success, returning each year from one bank of the Seine to the other, always upstream of the Eiffel Tower. Until it was slowed down by the great crisis of the 1930s.

Paris in the Roaring Twenties, this capital of love, which magnetized American writers of the Lost Generation, this capital of fashion, reigned over by Coco Chanel, the “garçonne” silhouette, and Gatsby-style elegance, this capital of literature and art, where Surrealism was in the ascendance, this capital of architecture, where Art Deco had supplanted Art Nouveau, this global capital of good taste and the latest trends now had its own boating event. The fluid lines of the mahogany motorboats echoed the stunning curves of the Bugatti Royale, on show just a short walk away.

Lindbergh had crossed the Atlantic, Aéropostale was pushing its lines as far as Buenos Aires, Alain Gerbault was sailing solo around the world, Josephine Baker was singing “J’ai deux amours”, and Maurice Chevalier was dancing the Charleston. Along the banks of the Seine, France’s presidents inaugurated the show and Parisians admired the turns of Chatou’s one-designs, while dreaming of river cruises or distant horizons. And they did more than just dream: both the wealthy and the passionate signed up to place orders.

Cargo ships rather than motorboats

War brought the festivities to an end. The October 1939 show was canceled. It did not return until 1947, on Quai Albert 1er, and could only partially lift the haze of the post-war aftermath. Although there were around one hundred exhibitors, the pre-war crowds were no longer seen at the foot of the Grand Palais. Parisians were no longer in the mood for samba or enjoying time on board sailboats or motorboats. Their thoughts were often more about finding a roof over their heads than a deck, and heating a home rather than trimming a sail.

The following year, in 1948, the show changed in terms of its nature, and maybe even its soul. Since recreational boating failed to attract enough interest, the organizers decided to call on the “great” maritime world for help. In doing so, they knowingly risked drowning yachting beneath the broader tides of maritime industry, whether merchant, military, or river-based. However, in 1952, they exhibited the cutter Kurun. But the cruiser of the circumnavigator Le Toumelin sparked less interest than the Alain Gerbault had a quarter of a century earlier.

Two years later, to try and generate interest again, they came up with the rather eccentric idea to exhibit a half-scale model of the future aircraft carrier Clémenceau, the pride of the national war fleet. That same year, President René Coty, a former member of parliament for Le Havre, long known as the capital of French sailing, inaugurated the “European Exhibition of Floating and Maritime Equipment”. Parisians and the media flocked to the riverbanks to admire this model. But this popular success blurred even further the image of an event originally devoted to yachting, and now presided over by a man of cargo ships and ocean liners, the head of Compagnie Générale Transatlantique…

The Paris of the 1950s was black with soot and ringed with shantytowns. It was slowly emerging from some dark years. Yet the City of Light was regaining its stature as the world’s fashion capital, with Christian Dior setting forth a new vision of elegance. Painting was being transformed by Noir et Blanc and abstraction, the Existentialists were filling the Latin Quarter’s cafes with smoke, students were split between Sartre and Camus, with the latter going on to receive the Nobel Prize. But the first ripples of the recreational boating revolution were not lapping at the foot of Pont d’Iéna bridge in Paris, but in Southern Brittany, where Parisians had made a new home, in search of freedom, sketching the hulls for the future “water rush”. The Vaurien and Corsaire were embarking on their first tacks, and would soon be on sale at the BHV department store. Many Parisians preferred small motorboats and waterskiing. The capital was buzzing with the infernal spectacle of the Paris Six Hours event, which electrified the 1955 show.

The boat show returned every autumn, along the riverbanks, but the rising tide of new leisure boating would soon overwhelm the very notion of a “maritime” event. Beneath La Défense’s soaring concrete spinnaker, a new exhibition devoted exclusively to canoes, dinghies and sailboats would not take long to win the “battle of the shows”.

Revenge of recreational boating

It was January 1962, the heating had not yet been installed in the CNIT, the RER train service did not exist, and “only” 50,000 Parisians, chilled to the bone, had dared to make the trip west to admire 300 boats. 300,000 visitors had crowded the banks of the Seine the previous October, after General de Gaulle inaugurated the 27th “International Boat Show”.

Yet the renegade exhibitors were delighted. The Jouët yard, in Sartrouville, in Paris’ outer suburbs, received 170 orders for its Golif, a remarkable 6.5m polyester liveaboard model.

Two years later, the Salon de la Navigation de Plaisance boat show at the CNIT had triumphed. It occupied four levels of the great shell at La Défense, showcasing dozens of units that inspired Parisians to dream and secured orders for the yards to keep busy throughout the winter months. A boating industry federation – Fédération des Industries Nautiques – was born. For 26 years, the CNIT show became the unmissable event for Parisians longing for a sense of escape and open horizons.

The yéyé generation filled the aisles of the CNIT, determined to overturn the old order. In the world of cinema, this was called the Nouvelle Vague or New Wave. In music, pop and rock swelled into a powerful tide. The baby boomers were dreaming of performance in Tabarly’s wake, and sailing around the world in the spirit of Moitessier. The sea came to Paris, General de Gaulle congratulated the winner of the Single-Handed Trans-Atlantic Race, and a dazzling array of innovations invited everyone to dream. Getting away was the new rallying cry for Parisians, swept up in the “water rush”.

In 1965, Michel Dufour unveiled his Sylphe. The following year, the Aubin yard presented the Muscadet. And a fleet of remarkable new vessels started to travel from show to show. Arpège, Sangria, Ecume de Mer, Sortilège, Romanée, Brise de Mer, Kelt 620, Gin Fizz, First and First 35, all brought by road to seek the approval of the Parisian public… For a quarter of a century, the boat show became yachting’s equivalent of Fashion Week. The middle classes reached for the horizon, and French recreational boating set out to conquer the world. In 1987, the Bénéteau yard unveiled the First 35s5, created by the architect Jean Berret and the designer Philippe Starck, during an unforgettable gala evening. Soon, the prestigious Pininfarina signature joined the celebrations.

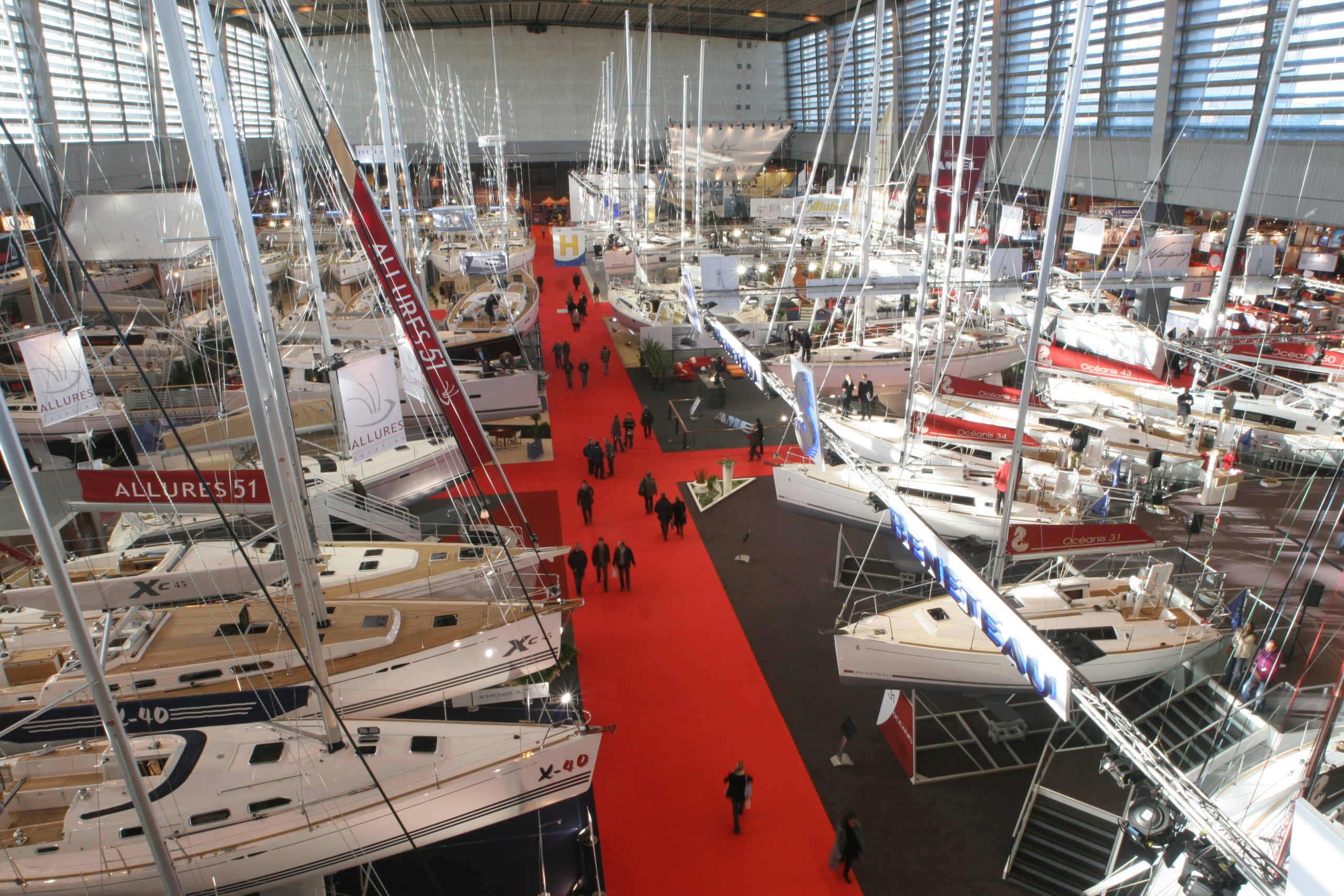

Then, in 1988, the show moved to Porte de Versailles, in an exhibition center built in 1923. It remained there for a third of century. Closer than ever to the heart of the capital. The vast halls were able to accommodate more sailboats, although the largest, like the CNB 76, shown in 2016, could no longer be exhibited with their masts fitted, as well as more motorboats, more new leisure activities, and more equipment suppliers. More events as well, with the Nuit Nautique, events for the television program Thalassa, meetings of industry professionals, the media and prestigious guests. The show presented legendary yachts, with the latest new models filling hundreds of pages in the specialist magazines.

Paris will always be Paris

However, over the decades, with evolving technologies, changing practices, new mindsets, economic constraints, logistical challenges, and many other factors, the Paris Boat Show gradually lost some of its magic. The French capital remained the world’s leading tourist destination. But the baby-boomer generation was aging. The new generations of Parisians were turning their thoughts to other pursuits. They were drawn to other adventures. Sailing and motorboating became just one of many others. Gradually, enthusiasm ebbed away. Exhibitor numbers were falling, and visitors too. The show adapted, trimmed its sails, and sought new forms of escape. But without success. Parisians still made up the majority of French recreational boat owners. Yet chartering was now on the rise, and purchasing a vessel was no longer something that necessarily happened in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower. In-water shows made the great indoor fair at Porte de Versailles seem old-fashioned. It was time for a change. In terms of both the location and the format.

In 2025, nearly a century after the Alain Gerbault had been exhibited on the banks of the Seine, the boating industry federation (FIN) wrote a new chapter in this story. The Paris Nautic Show opened its doors in Le Bourget, just a short walk from the airfield where Parisians had once given Charles Lindbergh a hero’s welcome. That was in May 1927.

Olivier Péretié