Jean-Marie Finot, The art of form

“Why are you laughing?”. It was impossible to have a conversation with Jean-Marie Finot without hearing this said repeatedly, after one of his dry, incisive jokes had set off a burst of laughter. All with a twinkle of mischief in his eyes, a wry smile, and a raised eyebrow feigning innocence. That day, he was telling us about one of his first encounters with the legendary American naval architect Olin Stephens. “I was impressed, of course, but mostly incredulous: we just could not seem to understand each other”. Stephens, in no uncertain terms, explained to his young French counterpart that the best boat is, above all, the one that sails upwind better than the rest. “On other points of sail, beam reach or downwind, any hull will move”, the master decreed. “No, what really matters is creating the most efficient waterlines for close-hauled sailing, with fine, deep, heavily ballasted and well-balanced hulls. That is what makes the difference”.

Warm and affable, Jean-Marie Finot could also express convictions forged of tempered steel, sometimes verging on sheer obstinacy. And now and then, he would step right over that line. On this occasion, he flatly refused to concede an inch. “No, I think you are mistaken”, he dared to reply. “A fast boat is wide but light, with shallow draft and strong form stability, so it can plane (rise up and ride on its own bow wave like an outboard) downwind, while remaining easy to handle. When planing, the speed differentials you can achieve far surpass anything possible when sailing upwind”. “Stephens,” Finot added with astonishment, “just did not understand. Or did not want to understand”.

And yet, these two wizards with opposing visions each ruled their own era. Jean-Marie Finot made Olin Stephens and his generation look outdated almost overnight. He dared to invent boats that were different: more powerful, lighter, faster, more spacious, and yet always elegant.

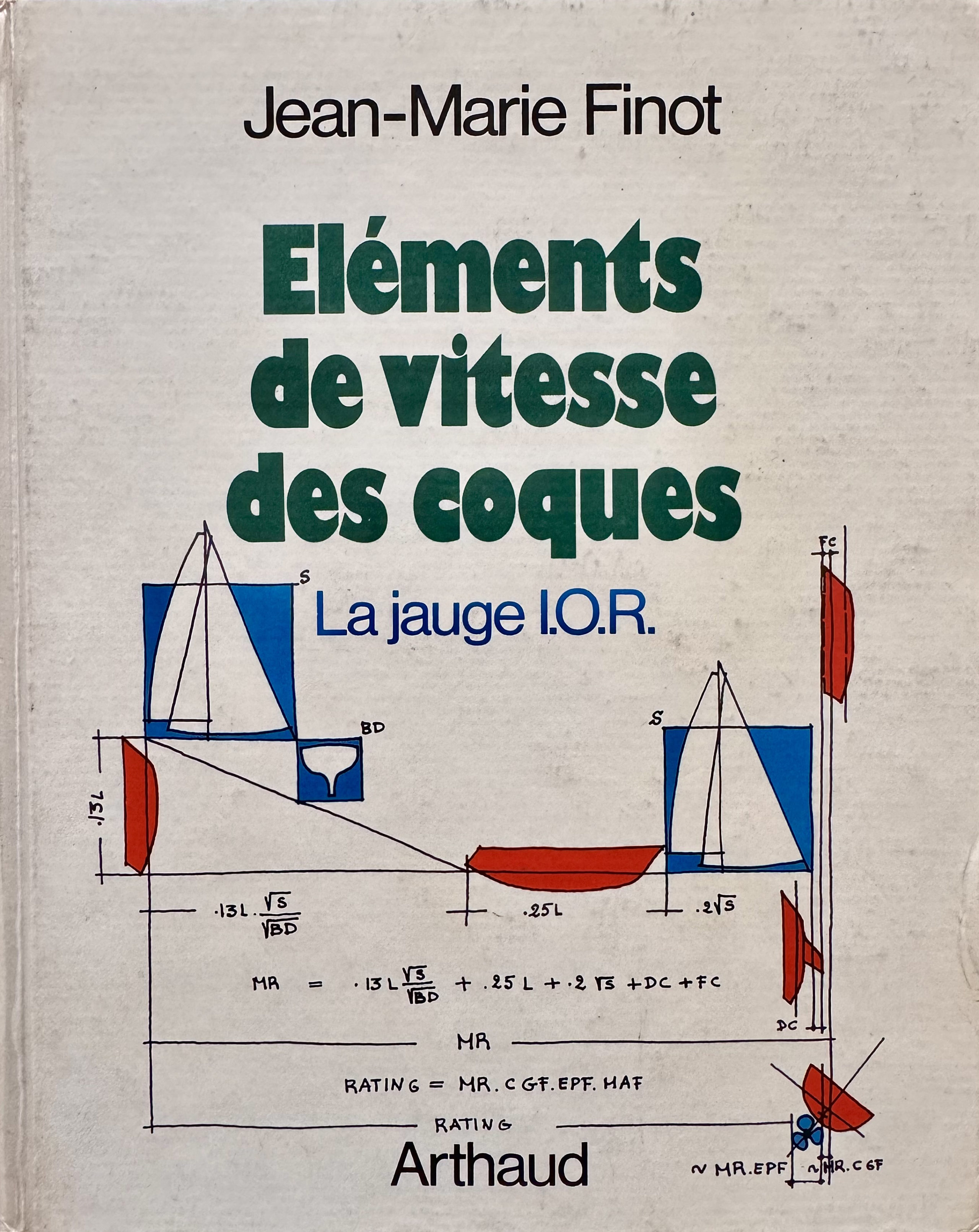

Our first encounter with this brilliant, tousle-haired genius dates back to the 1970s. We were preparing an interview for Loisirs Nautiques, the go-to magazine for amateur boatbuilders. At the time, the prototype Revolution (11.20m x 3.90m), crewed by a determined band of sailors from Saint-Malo, was causing a stir in British waters. And this plump, round-bellied fish looked nothing like the sleek British racers of the time, many of them designed by Stephens. Its extraordinarily wide transom – though hardly remarkable by today’s standards – was shocking back then. We asked Finot how a hull with such a generously proportioned stern could possibly perform well, especially upwind. What followed was a lesson in naval architecture, patient and insightful. Concepts like power, the distance between the center of gravity and center of buoyancy, stiffness under sail, the symmetry of heeled waterlines, everything that would later define Finot’s genius and be distilled into his delightful, hand-illustrated book “Éléments de vitesse des coques” (Arthaud), were laid out for us in a matter of minutes.

“It is actually the opposite”, Finot explained. “What makes a boat fast is its ability to carry sail”. To achieve this, you need to design a hull that is as powerful as possible, drawing its stiffness from its beam, while striving for the lightest possible displacement. And above all, you must avoid the traditional tapered stern, which was still widespread at the time, in order to avoid unnecessary weight. Révolution offered dazzling proof of this theory: it held its own upwind against its rivals, and soared away when downwind. Better still, with its flush deck and clipper bow, it somehow managed to project a new kind of elegance, perhaps even a timeless one.

For a young man from the Vosges, born in Épinal during the Second World War, daring to develop innovative concepts and triumph was no small feat. Especially since Jean-Marie Finot had no intention of becoming a naval architect. Traumatized by the wartime devastation in his region, this mathematical genius had decided early on that he would design houses. After completing France’s elite preparatory classes in mathematics, physics and engineering, he enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts to become an architect… plain and simple. And what about sailing in all that? After a few tacks in a dinghy on the Vosges region’s lakes, it was the Glénans sailing school that, like for many young French people of his generation, sparks a revelation, inspires a vocation, and shapes a destiny.

At Glénans, Jean-Marie falls in love with the sea and the shore, helps with logistics and, above all, meets Philippe Harlé. The inventor of the Muscadet opens a naval architecture office and takes on young Finot to help respond to the surge in demand. In 1968, the young assistant is not especially keen on making a career out of drawing waterlines, calculating prismatic coefficients, or debating the Froude number. Boats are for fun. Houses are serious. He will even design himself a home on the coast of Bréhat Island, seamlessly integrating it into the granite beauty of this landscape.

In the meantime, while he still intends to design buildings, he wants to sail. Since he loves the shores of northern Brittany, where the tidal range is enormous, he envisions for himself a sailboat of nearly 8m, equipped with a retractable centerboard. Around the same time, the prestigious Dutch yard Huisman, a specialist in aluminum, is looking to build a plan to enable racers to compete in the Quarter Ton Cup, the world championship for 8m live-aboard sailboats. Chance, or perhaps the intervention of Frans Maas, the renowned Dutch architect who Finot had met, opens the door to a collaboration between the builder Wolter Huisman and the young Finot… who modifies his plans and fits his prototype with a fixed keel. An aluminum prototype with hard chines, which he charmingly names Écume de Mer or Sea Foam. And although this Écume de Mer does not win the 1968 Quarter Ton Cup, it makes an immediate impression. Especially since it goes on to win many other events.

So much so that the La Rochelle-based yard Mallard decides to launch its series production… in polyester. Finot has just changed his status and scale. Life leads him to set up a naval architecture firm that takes the name Groupe Finot, because the young designer surrounds himself with fellow architects Laurent Cordelle (great racer, future winner of the Solitaire du Figaro), Gilles Ollier (future designer of legendary trimarans and founder of the Vannes-based yard Mutliplast) and Philippe Salles.

It is the early 1970s, and Jean-Marie Finot pushes the boundaries of his bold approach even further. His mathematical mind naturally leads him to computer technology to draw and test his hulls. And he is one of the first naval architects in the world to design his boats on a computer.

Écume de Mer enjoys phenomenal success. More than a thousand units will come out of the Mallard workshops. A little brother named Rêve de Mer soon follows in the wake of its elder sibling. And various aluminum units, such as the Brise de Mer, leave their mark. The Finot group also designs a number of racing prototypes, which will further enhance the reputation of its leader.

In 1977, now a renowned name in the world of recreational boats, Finot designs the First 18 for the Bénéteau yard, which has just converted to pure sailing. This small 5.5m cruiser, a kind of modern Corsaire, has all the qualities of a great boat. It embodies one of its creator’s convictions: a small boat can provide as much pleasure, if not more, than a large one. And the simpler a boat is, the more accessible that pleasure becomes. The 18 will be followed by a family of cruisers ranging from six to nine meters, all remarkable. In total, the Finot office will design around 60 units for the Bénéteau Group.

In 1985, Jean-Marie Finot hires the young Pascal Conq, freshly graduated in naval architecture, who will soon become his partner. And Conq is the ideal partner for Finot. Smiling, daring and creative, he designed a 5.50m liveaboard racing prototype – a Micro – and equipped it with a canting keel…

Yet in 1993, on the morning of the arrival of the second Vendée Globe, brilliantly won by Alain Gautier on a superb Finot ketch (the first of four successive victories by a Finot design in the solo round-the-world race), we were having coffee with the master. The terrace faced the sea, the weather was clear, the sea milky. “Remember what I am telling you”, Finot confided. “In my life, I will never design an IMOCA – a Vendée Globe type boat – with a canting keel. It is far too dangerous”. When in the 2000s, IMOCA boats with movable keels definitively prove their superiority over their fixed-appendage rivals, Jean-Marie Finot finally comes to accept the evidence. And Pascal Conq, the pioneer of movable appendages, plays no small part in that…

It is impossible to encapsulate the life and ideas of such a creator in a few hundred words. Saying that he left his mark would be the height of understatement. In the millennia-old saga of sailing, he simply sparked a revolution. Forty-five thousand sailboats, bearing his signature and that of his collaborators, can be found on all the seas around the world. At 70 years old, Jean-Marie Finot was still designing an original dinghy to open up the joys of sailing as widely as possible.

“Why are you laughing?”. His line is already missed by all those lucky enough to have known him. And who no longer feel like laughing.

Olivier Péretié