Electronics : Navigation for all

It was a November night in the English Channel. The ORMA class trimaran Broceliande was en route to Le Havre to take the start of the Jacques Vabre Double-Handed Transatlantic Race. Laid out on the sole bunk in the cramped cabin, Alain Gautier was asleep. Michel Desjoyeaux stood watch at the helm. A strong Force 7 westerly wind was driving the trimaran forward like a cannonball. Mich’Desj’ seemed to be hypnotized by the five-inch Brooks & Gatehouse screen showing a basic black-and-white chart. With the tide against them, and the wind fully behind them, he was not thrilled at the prospect of performing two jibes to pass through the notorious Raz Blanchard, between the island of Alderney and Cap de la Hague. He knew all too well that currents there could exceed 10 knots, and that wind-over-tide conditions could make the sea turn violent. Exactly the conditions they were facing. After carefully studying the electronic chart, he noticed a passage on the far side of the island. A narrow passage, certainly, close up against the rocks, of course, but one that made it possible to avoid the delicate maneuvers to change tack, always risky with a small crew and in conditions like this. The three-time winner of the Solitaire du Figaro decided to take this tricky route. Even in its still rudimentary form, the electronic chart allowed him to guide his boat through the ominously named “Swinge Channel”, in the middle of the night, and at full speed. A route that the Instructions Nautiques explicitly warned against in winds above Force 5…

This was in October 1999. Just a few years earlier, such a quick and simple decision would have been unthinkable. When GPS first appeared, giving the boat’s geographic coordinates, a small miracle in itself, these figures had to be manually plotted on a paper chart to determine its position. This was inconceivable on board a racing multihull flying along at over 20 knots in poorly charted waters. Having positions displayed in real time on charts changed everything.

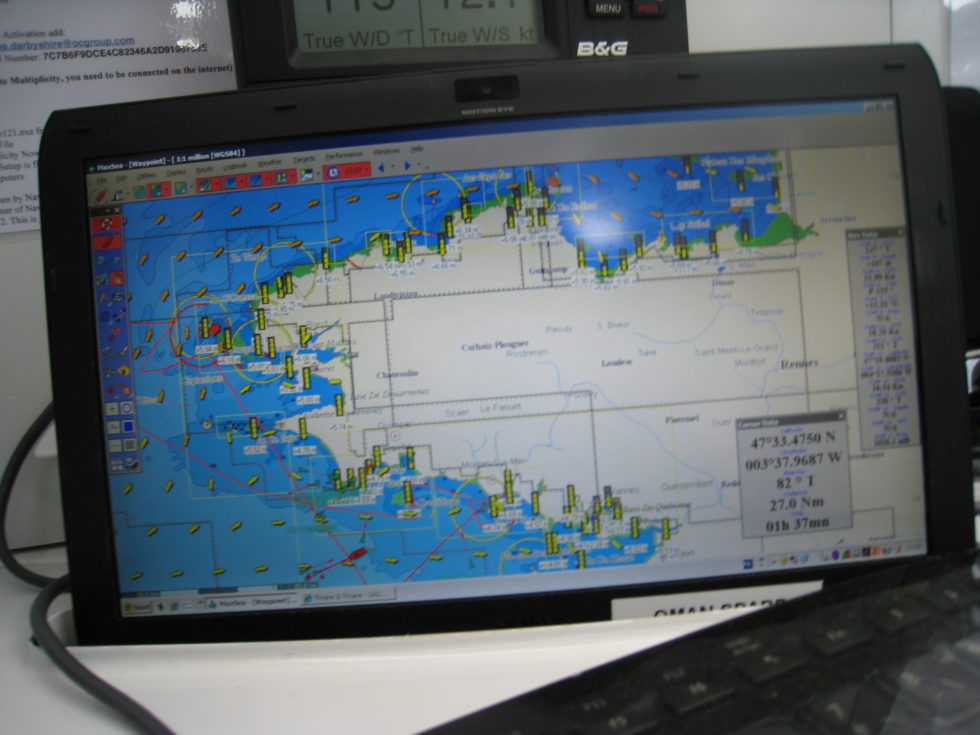

The decade from 2000 to 2010 ushered in another revolution. Color electronic charts, integrated with GPS and soon with autopilot systems, quickly became a common feature on the displays of chart tables and in the cockpits of recreational boats. Even when the Americans, who owned the global positioning system, temporarily degraded its accuracy for military reasons (Iraq War in 2003), everyday sailors could now confidently venture close to rocks or head offshore: they could see their position in real time on increasingly large and detailed color charts, although in some remote parts of the world, the reliability of these charts was still variable. The precision of GPS was getting close to 1 meter. Rival systems, such as Glonass (Russian), Galileo (European) and Beidou (Chinese), all accessible through a single receiver, made it possible to further increase this accuracy. The ancient art was now almost effortless.

Competition among the major marine electronics brands kept the prices of what were now known as “chartplotters” from soaring, while driving ongoing improvements with the hardware and the quality of the charts themselves – whether vector-based, which made it possible to display real-world imagery of navigation marks and other details, or raster-based, which faithfully reproduced paper nautical charts. By the end of the decade, the extraordinary rise of smartphones then tablets, with their charting and weather apps, opened up even more possibilities for electronic navigation.

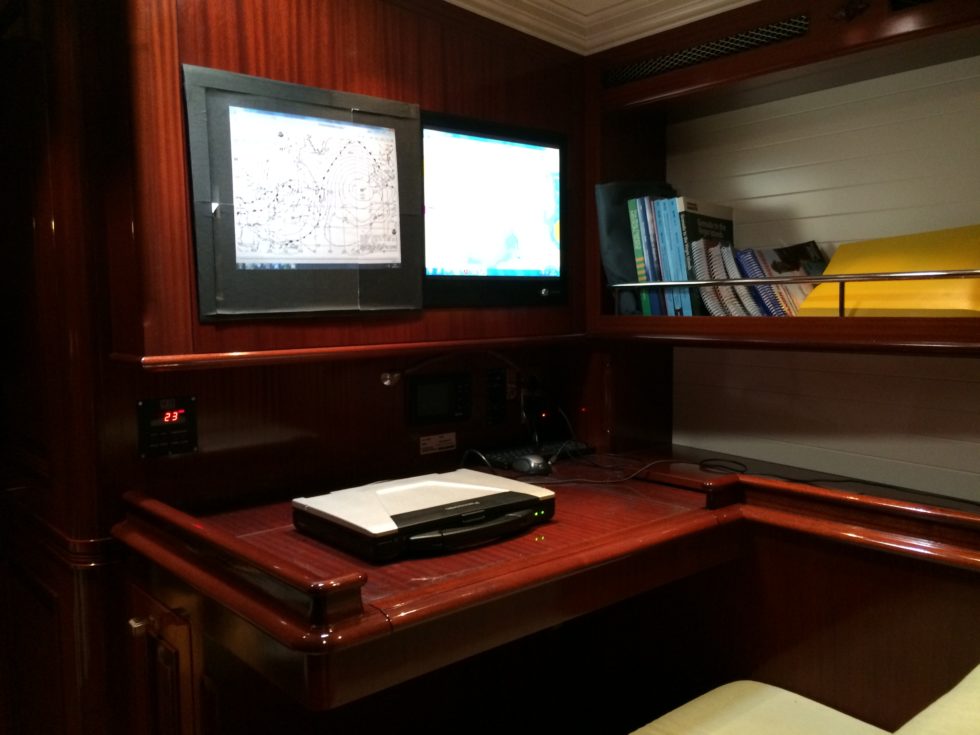

Faced with major firms from America and the UK, like Raytheon, which acquired Autohelm to become Raymarine, B&G, which was taken over by Navico in 2005 to join Simrad and the fish-finder specialist Lowrance, faced with the US-based Garmin, which entered the boating market in the early 2010s and bought out the chartmaker Navionics, and faced with Japan’s Furuno, the world leader for professional marine electronics, French companies managed to stand out. Thanks to their sense of innovation and the quality of their products. NKE, founded in 1984 by a passionate engineer from Brittany, became the go-to choice for both professional and amateur racers, with its displays, sensors and autopilots. The Basque firm MacSea, later renamed Maxsea then TimeZero, developed the first routing software aimed at the general public, before wisely partnering with Furuno to offer integrated hardware and software solutions. Adrena, based in Nantes and initially focused exclusively on racing, with its sophisticated routing software, also opened up to amateur cruisers.

Looking beyond the fundamental aspect of positioning and charting, the global electronics and computing industry’s spectacular progress also benefited the recreational boat sector, especially in France. The Automatic Identification System (AIS) for boats enabled the characteristics, heading and speed of all nearby commercial vessels to be shown directly on a recreational boat’s electronic chart. Before long, both sailing cruisers and fishing boats would be equipped with this essential tool, relegating radar, even though it had become lighter and more affordable, to coastal navigation in poor visibility.

Distress beacons, which previously operated exclusively on aviation frequencies, dramatically shrank in size and gradually expanded their frequency range. They became mandatory equipment for long-range offshore cruisers.

While smartphones reduced the use of VHF (short-range radio transceivers) to communications between boats and with harbormasters or rescue services, the Iridium satellite phone system gradually relegated SSB (single side band) radios, amateur radio sets, and weatherfax receivers like Nagrafax to the history books. It became possible to send and receive weather files, routing data and emails from onboard, even when far from land…

In terms of high-end autopilots, once the exclusive preserve of racers, remote controls, electronic gyrocompasses, and real-time wind and heel sensors gave ordinary sailors access to ever more reliable, simple and efficient systems.

It is no exaggeration to say that these continuous innovations have revolutionized recreational boat use. They have allowed even the most casual sailors to explore the farthest shores around the world, as well as the familiar coves and anchorages of home waters, places that were previously out of reach.