Infusion starts to spread

Plastic is fantastic*, and not particularly complicated. Just about anyone can set themselves up as a boatbuilder. Just as with a fulcrum one can move the Earth, with a good mold one can shape a hull. Think of Éric Tabarly, who salvaged the rotting hull of his old Pen Duick to create a mold, then personally applied resin to seven layers of glass fabric, bringing back to life his magnificent 1898 Fife design.

For decades, the technique for building fiberglass boats remained unchanged: once the fabric was laid inside the mold, it was stiffened by applying polyester resin with a roller, like painting a wall. You then simply waited for the resin to polymerize (harden), and a hull was born.

Well-suited to series production, relatively inexpensive, easy to implement, and not requiring highly specialized skills, the so-called “contact” method also had its drawbacks: it was impossible to apply a precisely measured and evenly distributed quantity of resin, or to avoid air bubbles despite using a bubble-busting roller. Hulls and decks built in this way often have uneven weight specifications and, at times, inconsistent structural homogeneity. This can lead, when poorly executed, to premature aging and even delamination, when the fiberglass layers begin to separate. Not to mention the issues surrounding pollution, as the open-air curing of polyester resin releases styrene, a particularly toxic compound.

To meet the extremely high standards of the aerospace industry, American engineers developed — and patented — a much more sophisticated technique: the SCRIMP process (Seemann Composites Resin Infusion Molding Process). They came up with the idea to inject the resin under vacuum using a plastic film that clung tightly to the part being produced.

The American yard Tillotson Pearson Inc., then one of the leaders in sailboat construction in the United States, decided to apply this process to build a phenomenally successful one-design, the J 24.

In Europe, a yard that emerged then quickly disappeared in Les Sables-d’Olonne and was looking to build a 24 meter motor catamaran with optimized weight specifications, decided to acquire a license for the SCRIMP process (for $25,000, including technician training). Unfortunately, this pioneer managed to sell only a single unit of his King Cat and soon went under.

King Cat’s employees and their expertise, tools and premises were just waiting for a new investor. An excellent regatta racer, and future bold and creative entrepreneur, Didier Le Moal had met Jeff Johnstone, son of one of the two founding brothers of the American firm J Boats, in July 1994 in La Rochelle. A fruitful encounter: six months later, Le Moal founded J Composites to build J models under license in Les Sables-d’Olonne. Since then, this yard has had a close partnership with J Boats USA.

At the dawn of the 21st century, Le Moal and his team had conceived a new 11 meter cruiser-racer designed to meet the expectations of European clients. To build in France this outstanding cruiser-racer unit, designed, like all modern J boats, by Alan Johnstone, the team at J Composites decided that infusion was the right approach to be adopted.

They aimed to offer a hull that was light and stiff, as strong as it was high-performing. At first, the J Composites pioneers subcontracted the construction of this future star to the former King Cat workshop, which was quickly integrated into the new yard.

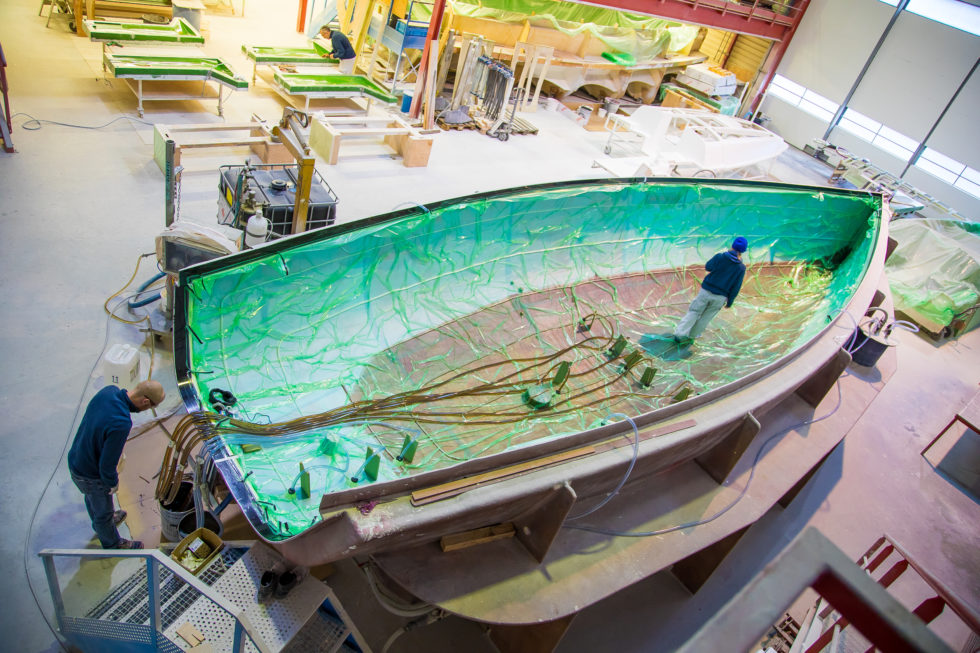

The specialists from King Cat used to inject resin under vacuum conditions through a spiderweb of distribution hoses and strategically placed injection points. They covered the entire assembly with a flexible, airtight plastic membrane – the “vacuum bag” – whose edges were sealed to the mold. A vacuum pump then allowed the bag to compress the fabric layers while the resin, drawn in by the vacuum, slowly and evenly saturated the entire hull. The amount of resin used could therefore be controlled to the nearest gram. J Composites was producing hulls that were lighter, more consistent, and stiffer. Ideal to ensure excellent sailing performance levels, whether racing or cruising.

With its balsa sandwich hull, the J 109 became the first production monohull built using infusion in Europe. Hull number one left the yard in 2001. The J 109 was soon dominating in races. And in order books: this precursor to the modern J range sold 400 units. It was the first link in a family of remarkable yachts, now built using closed-cell foam sandwich construction and an infusion technique that has continued to evolve.

From the late 1990s, builders of cruising catamarans, which were seeing rapid growth, also turned to infusion. As these units became increasingly equipped with domestic comforts for on-board living, it became crucial to lighten their hulls.

As Bruno Belmont, one of the founding figures of the Lagoon brand, explains: “That is the reason that naturally led us to use infusion: it was not all that difficult to work around the SCRIMP patent”.

Because the learning curve for infusion can be long, because it demands careful execution, and because it uses more consumables – the vacuum bags cannot be recovered – this “premium” construction method was, for a time, limited to small or mid-size companies. Larger groups, on the other hand, tended to use resin injection, a similar process, but one in which the plastic film is replaced with a hard two-part mold into which the resin is injected. The Bénéteau Group, for instance, uses injection molding to build the decks of its models.

On average, infusion is 30% to 40% more expensive than contact application, and this naturally impacts the price of new boats. However, units built using infusion age well and retain a higher resale value than those built with other methods… In the 2000s, only a few yards in Brittany specializing in high-performance monohulls, such as JPK Composites, Pogo Structures or IDB Marine, also chose to adopt this technique. But, as we have seen, the cruising catamaran builders had not waited for them to lead the way. The monohull builder Dufour joined them soon after. Specialized in small and mid-size powerboats, the Charente-based yard Ocqueteau also converted to this process.

In 2016, the SCRIMP process patent entered the public domain. The future looks bright for infusion.

*See the article “Innovation” in the 1950-1960 section.

https://museedelaplaisance.com/en/collection/plastic-fantastic