Motorboating turns 100!

As you stroll along the docks of any French marina in the early years of the new century, it is easy to notice the growing presence of increasingly imposing motorboats. The size of the most visible boats is clearly on the rise, even though the vast majority of registrations, as has been the case for years and in a less spectacular way, still go to units under six meters. This trend is not really new, but it does raise questions about the future of the infrastructure in place and the capacity of maintenance and repair yards. The benchmark of recent times, when a 9-meter (30-foot) hull was considered a “beautiful” unit, seems to be rapidly shifting towards 12 meters (40 feet), or even 15 meters (50 feet), with a range of consequences, from purchase prices to operating costs and maintenance.

Broadly defined during the 1960s, motorboating for leisure is still, some 40 years later, structured around a handful of core types of boats. While lengths, power ratings, on-board equipment and comfort levels have all evolved significantly, the way boats are used – and how frequently – has remained largely unchanged, especially in the Atlantic and Mediterranean. This is why boat builders’ catalogues from the 2000s still include the same categories as previous decades, from semi-rigid models to 15-meter offshore cruisers (open, hardtop or flybridge), open hulls (generally under 6 meters with a central console – bowrider or walkaround), day cruisers with small cabins, pilothouse or “sport fishing” boats, and trawlers. However, while the terms remain the same, and become increasingly anglicized in other languages, the realities that they cover reflect another underlying trend in the early 2000s: premiumization. This pursuit of style, comfort and even luxury has been developed by the yards through collaborations with high-profile designers, particularly from France and Italy, creating original concepts and distinctive lines, crucial components of an increasingly sophisticated brand image.

Design takes center stage

At the same time, benefiting from the declining appeal of American models in Europe, and in France in particular, the sector’s leaders from France, Italy and Germany have doubled down on their efforts to renew their offerings across many of the most promising segments.

In the open-hull segment for instance, Bénéteau’s Flyer moves into its fourth generation with 24 models, ranging from the most accessible 5-meter version to a 12-meter cabin cruiser, featuring a range of different equipment (6.5-meter convertible with a traditional cockpit, 7.70m walkaround or 8.80m sundeck).

Another example of this premiumization is the Antares range from the 2000s, created by Sarrazin Design, clearly moving away from its original “sport fishing” roots to enter the more distinctive world of motor cruisers, while focusing on its core qualities in terms of performance on the water. Under the Monte Carlo label, the French group based in Vendée launched a new series of high-performance units (27, 32, 37, 42 and 47 feet) infused with Mediterranean flair and luxury thanks to the creativity of Italian designer Pierangelo Andreani. The same designer was also entrusted with creating the models from the Gran Turismo series, setting out the yard’s choice to establish itself in these highly competitive segments. Even the traditional trawler has seen its concept refreshed and modernized, becoming quicker and more comfortable. At Jeanneau, the new Cap Camarat and Merry Fisher models lead the way, alongside the NC concept from Camillo Garroni, ranging from 9 to 14 meters, establishing themselves to dominate this race towards premiumization.

This decade from 2000 to 2010 also sees the emergence of a niche “neo-retro” trend, as in the auto industry (Mini, Fiat 500, etc.), taking a fresh look at traditional styles of coastal fishing boats, from Italy with Apreamare to New England with Mochi Craft’s elegant lobster boats, like the Dolphin 44. What is less visible is not neglected either, with hulls becoming more efficient and high-performing thanks to the capabilities of digital design. Propulsion and engine systems remain relatively unchanged, with a majority of diesel units featuring either shaft drives or stern drives for inboards and outboards for the other models. At the same time, two opposing trends are converging, with, on the one hand, growing environmental pressures, and on the other hand, the increase in boat sizes and engine power, for inboards and outboards in particular. Increasingly restrictive exhaust emission regulations are adopted in May 2003 by the European Parliament and Council, and come into force in 2005 and 2006.

At your fingertips

In 1960, at the New York Boat Show, Volvo Penta made a significant technical and commercial breakthrough with the launch of its Aquamatic sterndrive. This compact unit was able to replace the traditional inboard shaft and propeller setup with a drive system offering the flexibility of use associated with outboard engines (see The sterndrive revolution – 1960).

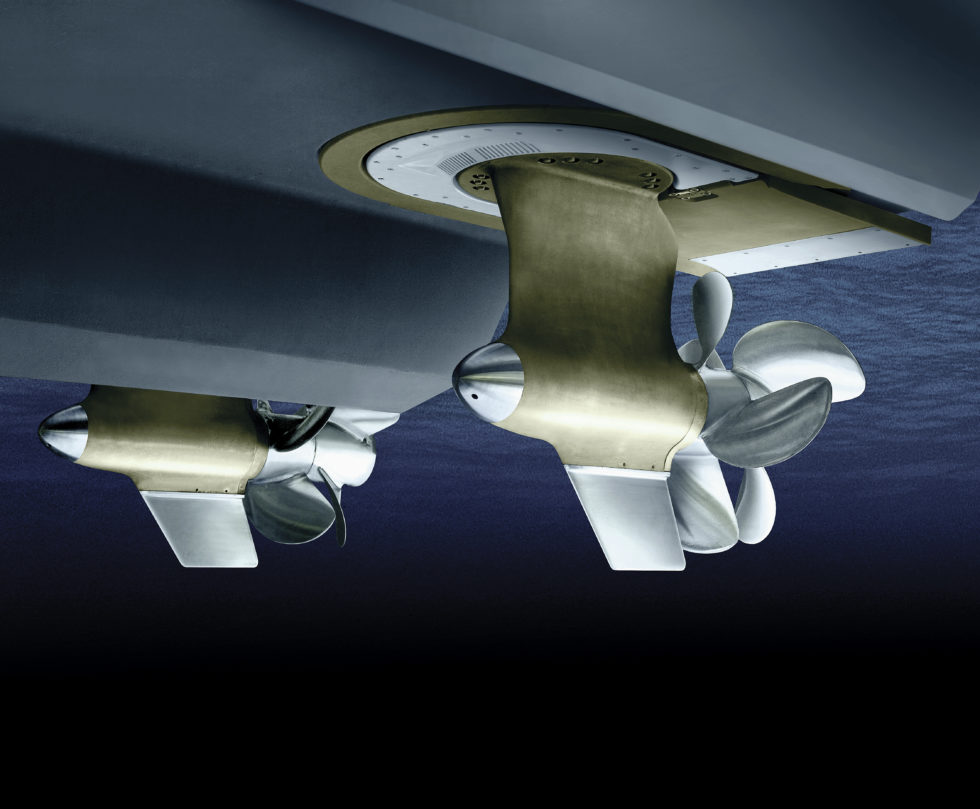

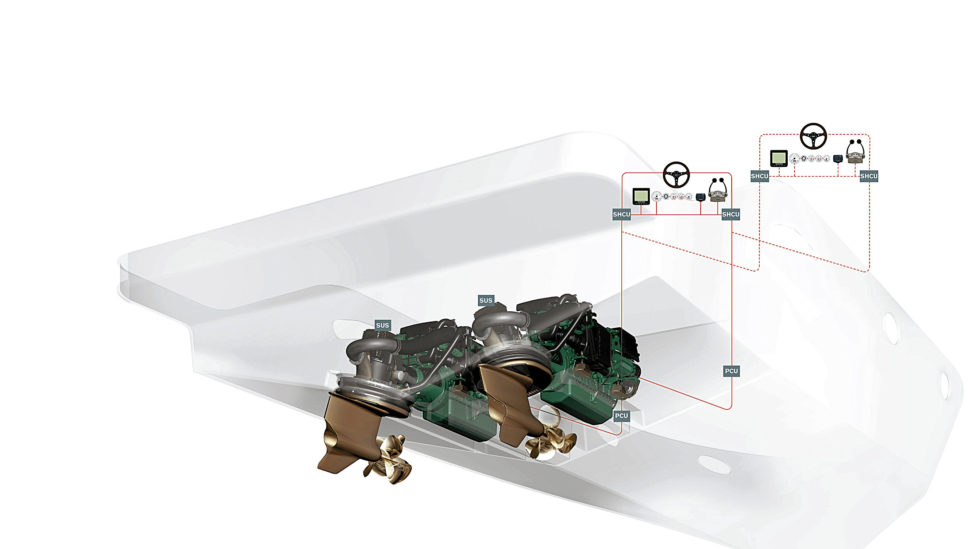

More than 40 years later, in 2005, at the London Show this time, the Swedish firm breaks new ground again, albeit on a less universal scale, with its IPS in-board performance system, more commonly known as the “Pod”. Initially tested on large commercial vessels, this new system was then adapted for use on recreational boats. This pod is a drive unit mounted beneath the hull that can rotate 360 degrees, driving two forward-facing, counter-rotating propellers that pull the boat through the water. Quite complex and costly to install, this system is reserved for boats from 50 feet up. For shorter units, Volvo developed the Zeus system, based on the same principle, but more traditionally configured with counter-rotating propellers that push rather than pull. In both cases, twin-engine boats fitted with these systems benefit from a major advantage in terms of easier handling, performance and reduced fuel consumption, as well as vibration and noise levels. As in 1960, success follows swiftly, and by the end of the decade, nearly a hundred models are equipped with these systems. They include the larger units from the Monte Carlo, Gran Turismo and Swift Trawler lines developed by Bénéteau, the first European yard to adopt this innovation, alongside models from Jeanneau and its Prestige brand, whose success has grown year after year.

Torn between two worlds

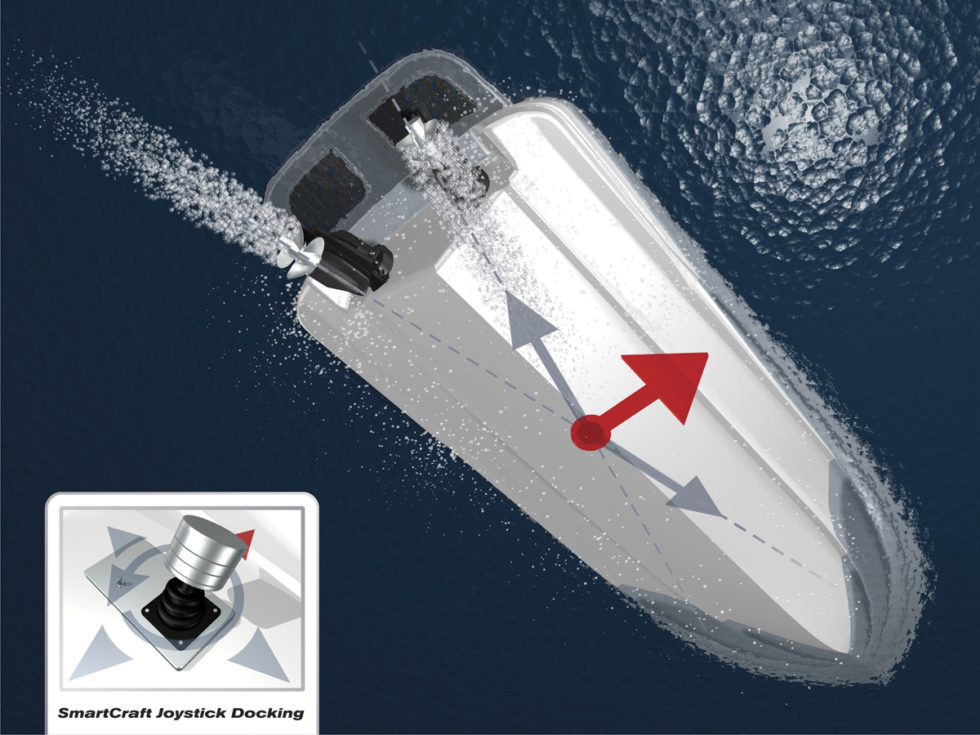

The IPS and Zeus systems go hand-in-hand with another revolution, with the joystick, which is also introduced in 2005. This single control stick fundamentally changes how boats are maneuvered, sending highly precise signals to the steering, transmission, engine speed and other controls. This highly efficient principle will quickly be adopted by other engine manufacturers, including Mercury and Yamaha. Such a system, based on electronics and the development of the on-board communication network, once again confirms the unstoppable rise of data transmission across all the features found on a boat.

The National Marine Electronics Association (NMEA) standard, rolled out from 2004, supports the integration and simplification of connections between the various sensors and display units.

With the ever growing range of equipment available, this American standard changes the landscape in terms of connectivity. A single cable can be fitted with as many quick-connect ports as needed to transmit all the information from various sensors to digital displays, from speed to fuel tank levels and engine data.

Among the latest “luxuries” gradually being introduced to motorboat users, the installation of a gyroscopic stabilizer on units as small as 7 meters stands out as one of the most discreet and unexpected new developments from this decade of technical progress.