Calm seas, poor visibility

The boat industry is no stranger to turbulent times. Its close ties to the sea seem to have placed it at the forefront of cyclical storms, seen almost every decade since its emergence and its expansion in the 1960s. When storm clouds gather, industry leaders, often interviewed by the press, tend to remind us that “a boat is not a necessity”, tacitly acknowledging the market’s inherent fragility. However, the battle that they must all fight each time to stay on course and right their ship is no less daunting.

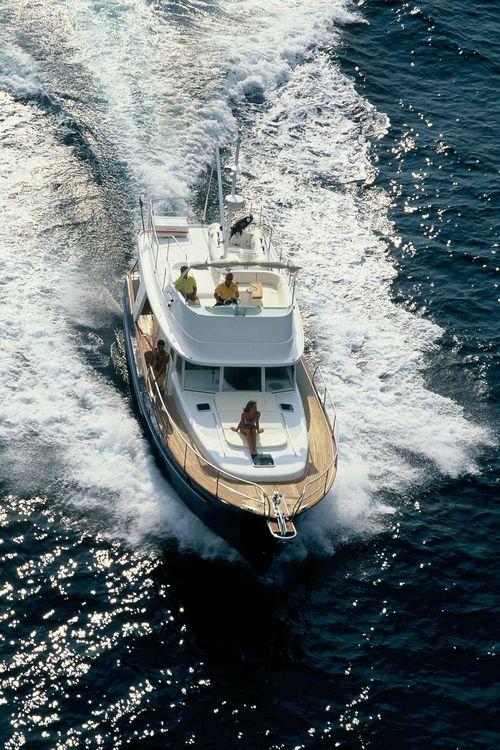

Around a decade after embarking on a slow recovery from the global crisis sparked by the Gulf War, and after making progress with production, revenues and exports, the French motorboat sector once again sees its hopes for stable development threatened by another market downturn. In this already tense climate, the worst is still to come, as the next major crisis of 2008 is not yet on the horizon. Between 1997 and 2004, French motorboat manufacturers achieve average annual growth of over 20%, in a market still largely dominated by recreational motorboating.

French and Italians leave the Americans in their wake

In 2004, sales to foreign clients, primarily in Europe, recorded further progress compared with the previous year, with French yards performing strongly and ranked third in Europe, behind Italy and the United Kingdom. Alongside this, the appeal of American products, which once set the trends for others to follow, faded to a great extent, faced with the all-conquering creativity of French and Italian firms. 2005 confirmed this encouraging momentum. However, the wave of new motorboat registrations began to ebb as early as 2007, with a decline of around 2% versus the previous year. This is due to a number of factors, with some linked to the general economic climate, as well as structural aspects, including the persistent issue of infrastructure to accommodate new boats. As in the past, many professionals pointed to the shortage of available berths in marinas, a key factor for growth, especially as boat sizes continue to increase. However, unlike economic fluctuations, which can move quickly, building new marinas or expanding existing facilities is a complex and lengthy process, preceded by increasingly stringent studies in line with environmental protection requirements.

Life after death for old hulls

This issue with facilities, affecting both motorboating and sailing, was now combined with another major environmental concern, also common to both sectors. The fate of boats when they reach the end of their lives became a growing concern from the mid-2000s, reflecting an awareness campaign launched in 2003. In 2005, the French boating industry federation (FIN) forecast that the tonnage of waste from decommissioned boats – both sailing and motor – would reach 25,000 tons by 2015, with engines alone requiring specialist treatment, separate from their hulls and accessories. Manufacturers, repair and maintenance yards, and local authorities were all encouraged to carry out in-depth work on dismantling and depollution once boats reach the end of their lifespan of around 30 years. In an uncertain economic climate, the promoters of this initiative were able to emphasize not only the environmental stakes, but also the economic value of the new jobs created, moving away from the practices of burning or sinking stored or abandoned hulls. Depollution and dismantling could, in time, represent a significant share of the boat sector’s activity as it moves into a more sustainable era. Depollution, the first phase, would make it possible to recover all the fluids, toxic products, and severely degraded or hazardous materials. This would be followed by dismantling, with the boat disassembled and its components sorted for recycling. Since motorboats are built primarily with resin and fiberglass, the treatment and reuse of substantial quantities of this type of “plastic” represents a major challenge for the sector. However, by the end of the decade, they also offer opportunities that some stakeholders hope to capitalize on in the future.

The domino effect of the 2007 financial crisis

The 2008 economic crisis, triggered by the collapse of the American mortgage market the previous year, will leave a lasting mark on modern history due to its global spread and long-term impacts. Without revisiting the well-documented mechanics of the crisis, a few figures offer a sense of its scale.

According to the Banque de France, between 2007 and 2010, unemployment in the United States climbed from 4.6% to 9.6% of the active population, while public debt surged from 86.4% to 125.8% of GDP. In the Eurozone, these figures shifted from 7.5% to 10.2% and from 75.9% to 101% respectively. In France, the boat industry was severely impacted from autumn 2008, the traditional period for taking orders for new units. Uncertainty about the future led buyers to put their plans on hold. Many manufacturers, having invested heavily in previous years to improve their productivity, suddenly found themselves in difficult waters. Faced with a serious crisis, adaptability is crucial. But courage and resources are also necessary. In France, the Bénéteau Group quickly grasped the severity of the situation. As early as April 2009, it announced a restructuring plan aimed at reducing its workforce by 1,600 positions. Thanks to numerous adjustments, the number of forced redundancies was ultimately limited to around a dozen staff. At the same time, the company was preparing to ramp up its competitiveness by looking into opportunities for external growth